Submit Your Remarks to the Forest Service Here

One of the highlights of my conservation career occurred during the summer of 2013, when I recorded the plaintive howl of OR-4 during an Oregon Wild staff outing in the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest along the eastern end of the Wallowa Mountains. It was a chilling, fascinating moment, and along with seeing a wolverine at Glacier National Park, as raw an interaction with wildlife as I’ve had. Local trackers who were with us estimated the great wolf was within 50 yards of our group.

While the intent of our visit wasn’t to disturb or even approach the den of the Imnaha Pack, we did want to sample the remote wilderness where the pack had made its home. This is where the amazing saga of OR-7, who was one of OR-4’s sons, began in 2011. Later becoming known as Journey for his determined solo trek southwest through Oregon and then south to California, OR-7 became the first American gray wolf known to reclaim its species’ habitat west of the Cascade Range after being nearly hunted into oblivion some 80 years earlier.

Today, however, the remote wilderness of Wallowa County is being threatened by the kind of megalomaniacal resource extraction commonplace throughout much of Oregon. Part of the reason the Imnaha Pack found the region to be a suitable home is because of the area’s remoteness. But that’s now threatened by the deceptively named Morgan Nesbit “restoration” project. Pro tip: Anytime a management agency like the Forest Service uses the word restoration in what is otherwise a pristine area, it’s a euphemism for “resource management,” i.e. logging.

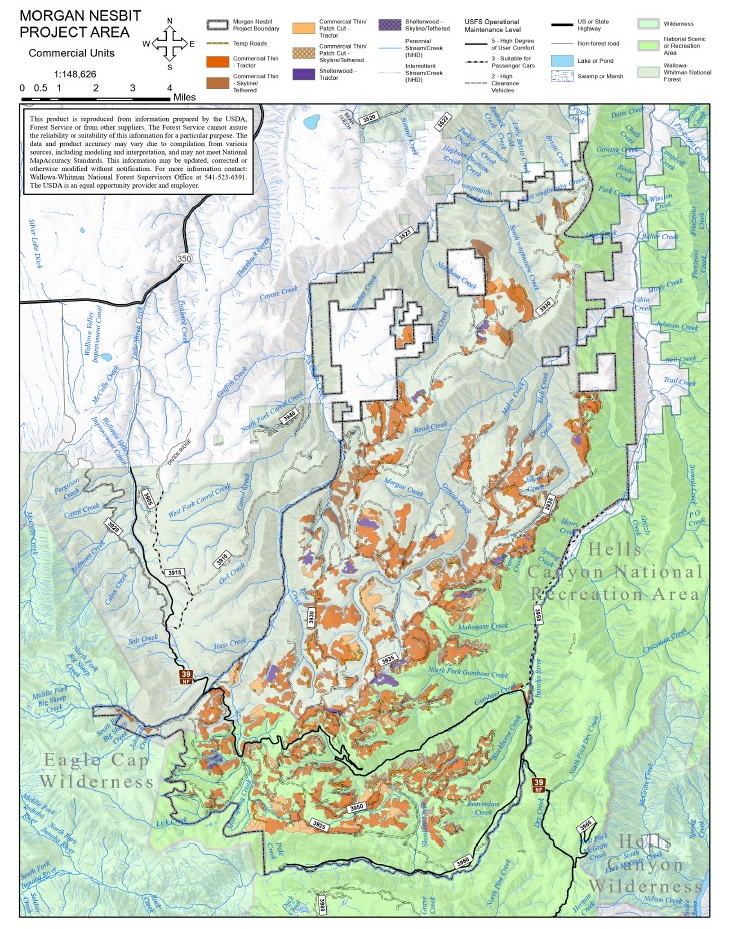

Totaling some 87,000 acres, the Morgan Nesbit proposal extends from the eastern edge of the Eagle Cap Wilderness in the Wallowa high country to the Snake River gorge of Hells Canyon National Recreation Area along the border with Idaho. And while the Morgan Nesbit plan is not only unacceptable given the area’s largely roadless quality and that native Nimiipuu communities continue to make this remote land home, scientists have noted the region’s importance as a wildlife corridor threading the miles of forest and meadows between the ice-clad peaks of the Wallowa range and the mile-long drop into Hells Canyon.

As an abundant, biodiverse region where the ecosystems of the Northern Rockies, high desert, and Blue Mountains meet, the area is home to an array of endangered fish, plants, and wildlife — all part of the reason the Eagle Cap Wilderness was preserved as one of nation’s first designated Wilderness areas with the passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964. The area has long been so remote and wild, in fact, that in 1940 the Forest Service signed off on a wilderness management plan when it was designated as a primitive area — the precursor to today’s National Wilderness Preservation System.

While some portions of the Morgan Nesbit project may merit cautious consideration, the clearcuts, construction of 23 miles of new logging roads, large-tree logging, and aggressive thinning in previously unlogged forests are all hallmarks of destructive, industrial logging. And as is so often the case with Eastern Oregon “dry forest” logging proposals, it appears the Forest Service is ignoring more pressing restoration needs like damage from cattle grazing and large and medium-diameter logging in the name of wildfire suppression.

Our friend Jamie Dawson with the Greater Hells Canyon Council recently posted a blog about the Morgan Nesbit logging proposal, and the map below similarly details some of the proposed logging areas.

If you’d like to share your thoughts and make a comment to the Forest Service, please do so by this Friday, April 7th.

Share with the Forest Service why this region means so much to you and your family, especially if you have a relationship with the area. Encourage the agency to focus on legitimate restoration needs rather than supporting industrial uses of our forests, as the consequences of poor management falls on the backs of our larger environment by destroying perfectly good, taxpayer-owned, carbon sequestering habitat that’s worth more to our good health standing than cut.

Specifically, ask the Forest Service to:

- Give serious consideration to all perspectives, including tribes, conservationists, and people who may only visit the area.

- Honor the biodiversity and complexity of the landscape with a thorough analysis and ecologically-sound proposal.

- Leave big trees and mature old-growth areas untouched.

- Prioritize habitat for fish and wildlife as well as the climate values of our forests.

You can also encourage the Forest Service not to:

- Build new roads that permanently fragment the landscape and harm local wildlife corridors and environmental values.

- Cut in roadless areas or areas proposed for protection and conservation management.

- Engage in logging on steep slopes.

Again, you don’t have to be an expert. That should never preclude you from making a comment. Share who you are, why you care, and what you hope the agency will consider.

Help preserve this special, wild area of northeast Oregon that’s so far off the grid it’s one of the few places in the lower 48 states where you may hear the howl of wolves under nighttime skies alight with stars far from light pollution — as remote a setting as any in the continental United States. And what a special resource that is.

If you have questions, or would like to discuss the Morgan Nesbit logging project further, I’d encourage you to connect with my friend and former Oregon Wild colleague Rob Klavins.

Photos of the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area and Wallowa-Whitman National Forest © 2013 Tommy Hough, all rights reserved.