By Mia Taylor with Tommy Hough

As California finds itself amid another devastating wildfire season, there’s perhaps no more timely or critical environmental topic than the logging of our National Forests, which the Trump administration has been actively encouraging and fast-tracking past long-standing environmental review under the discredited guise of wildfire suppression.

Earlier this month San Diego County Democrats for Environmental Action club hosted an Environmental Report featuring presentations from the staff of the Central Coast-based Los Padres ForestWatch (LPFW), an organization quite literally on the front lines of this issue in California.

The presentation featured a particularly powerful presentation from LPFW conservation director Bryant Baker, who revealed that logging practices occurring on National Forest lands are often far more environmentally destructive than helpful, with the work being done primarily for the benefit of the commercial timber business — not the public or the environment. What’s more, in the wake of such logging, forests are often left more vulnerable to wildfire than they were before. This scenario just played itself out, again, with the catastrophic wildfires to the north in Oregon.

And in what should come as no surprise, such corrupt, misguided and environmentally devastating practices are occurring more frequently under the Trump administration and their appointees.

While large-scale logging of old-growth and mature forest was largely discontinued in National Forests in the Pacific Northwest following the science-guided and Clinton administration-brokered Northwest Forest Plan in 1994, the four Southern California National Forests (Angeles, Cleveland, Los Padres, San Bernardino) were generally left out of the those considerations due to their lack of overwhelming stands of marketable timber. Unfortunately, under Trump, large diameter trees are once again being cut en masse by the Forest Service throughout the west, and with the least amount of environmental oversight and review since the “bad old days” of the federal timber-cutting frenzy of the late 1980s.

“We’re seeing this a lot. It’s only getting more intense under the Trump administration, and it’s getting more brazen,” Bryant Baker explained.

The Forest Service’s current “forest thinning” proposal in the Pine Mountain area in the Los Padres National Forest is just one example of the devastation and corruption wrought by increased logging efforts, fueled by the breathless urgency to pointlessly destroy habitat and cut the most mature, fire-resistant trees “before the next wildfire occurs.”

At Pine Mountain, the Forest Service is proposing logging and chaparral removal on some 755 acres of land made up of a mixture of old-growth conifer stands of Jeffrey and Coulter pine and ancient White fir. Located near Mount Pinos and the recreation sites and trails of the popular Frazier Park area, Pine Mountain includes a diverse array of Southern California ecosystems in which both healthy and dead trees, called snags, would be cut as part of this proposed project using heavy equipment ranging from masticators to chainsaws. The agency has made it clear a commercial logging or timber sale is likely.

“The Forest Service has acknowledged they’re looking at a commercial timber sale to do this,” said Baker. “This is what we’re increasingly concerned with on these types of projects. They’re really aimed at trying to remove certain size trees that are marketable and can be a source of revenue either for a private company that comes in and does the work, or as a direct timber sale where the Forest Service would sell the timber and keep the money for revenue.”

The Forest Service has established a handful of limits for the project with regard to tree cutting at Pine Mountain, based upon tree diameter. The first is it will remove trees less than “24 inches” in diameter.

In other words, the Forest Service will allow, without any questions asked, the removal of any trees that are less than two feet in diameter. In selecting that measurement, the Forest Service is relegating to an old public relations trick of making trees seem smaller than they actually are, and that these removals are inconsequential. But that couldn’t be further from reality.

Even to a casual observer, a 23-inch tree is hardly small or inconsequential. “This is what the agency calls a ‘small’ tree,” explained Baker. “We disagree. We do not believe this is something that can be categorized as a small tree, but the agency is essentially telling the public they’re only going to be removing small trees.”

What’s more, a 24-inch tree, as Baker explained, just happens to be a size that commercial timber mills welcome because they tend to be very straight, non-damaged trees. For a timber warrior like founding club president Tommy Hough, who worked on logging issues with the Missoula-based National Forest Protection Alliance in Seattle and as a staff member with Oregon Wild, the similarities to arguments the Forest Service, Bureau of Land Managment (BLM), and Big Timber use to justify logging in the Pacific Northwest are all too familiar.

“The Forest Service still operates on the antiquated 1930s concept of ‘multiple use,’ and sawmills are still largely equipped to work with large diameter trees,” said Tommy. “The timber industry never really bit at the idea of selectively removing smaller-diameter trees out of plantation forests because their mills simply aren’t equipped to work with them other than grinding them into mulch.”

The second parameter for the Pine Mountain project is that the Forest Service will remove trees up to 64 inches in diameter.

“The Forest Service is saying it can remove trees up to 64 inches for very vague reasons,” said Bryant. “They may cite safety reasons, or if the tree is impacted by dwarf mistletoe. But safety is undefined. They don’t really talk about what that means. We’ve seen this before in other National Forests and other projects, and these types of stipulations get abused because they’re so vague.”

According to Tommy, “Big Timber wants to sell 2 x 4s to China, and both Republican and Democratic administrations typically want to enable that. So they look for reasons to go cut big trees, wherever they may be accessible, even though the older the tree the more fire-resistant it is because of its thicker bark. Go walk in any mature forest and you’ll see plenty of burn scars on older trees.”

Lastly, the Forest Service will allow trees impacted by dwarf mistletoe to be removed. The devastation of this stipulation truly needs to be put into perspective. Dwarf mistletoe, as Bryant explained, is an important native plant species that occurs in these forests naturally. It’s an important component of mixed conifer forests, serves a vital ecological function, and increases the diversity of bird species.

Furthermore, most trees in the Pine Mountain area have some amount of dwarf mistletoe. Translation: When you also include the stipulation that trees with dwarf mistletoe growth can be removed, the Forest Service is allowing the cutting of all trees that are present in the project area – with no real or substantial limits at all.

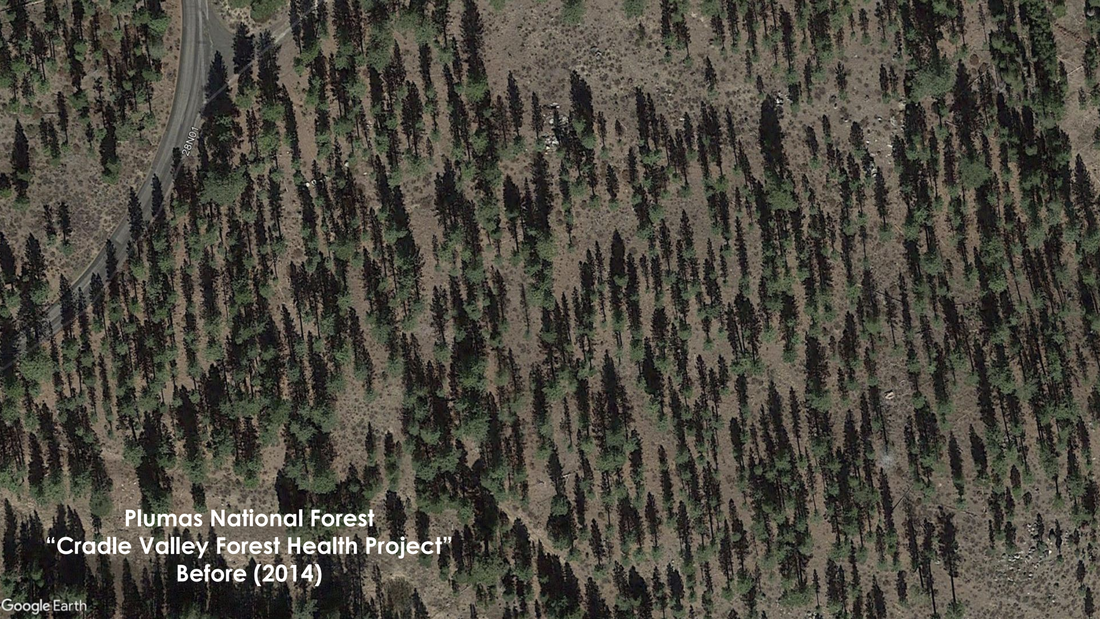

Perhaps the most egregious aspect of these so-called fire suppression projects is the way the U.S. Forest Service has been directed to circumvent the typical review process. Using the cover of what’s known as a “categorical exclusion,” the Forest Service can proceed on a project without even providing an environmental impact statement (EIS) or environmental review. Past examples of categorical exclusion logging projects are disturbing at best. The before and after images of a similar project in the Plumas National Forest in Northern California, which was conducted using the same justifications and language as the Pine Mountain project, demonstrate the vast devastation.

The first image is an area the Forest Service claimed was “too dense.” The agency suggested that if a fire came through it would destroy the forest and put communities at risk. The removal of biomass, the agency said, was essential and would be ecologically beneficial. The second photo, which shows the heartbreaking aftermath of such efforts, speaks volumes about the environmental destruction that took place.

“This is not a low impact activity,” said Bryant. “This is extremely soil disturbing. This was all done for commercial timber sale. They said this was for forest health and to protect communities. This was a backcountry project that was nowhere near communities and we’re seeing this all over California.”

Finally, it must be understood that these projects do not necessarily aid in wildfire suppression. In fact, they have the exact opposite result. According to Bryant, “You’ll find a lot of non-native grasses in these really disturbed areas, which only make fire more likely and make fire spread more quickly. What we’re finding is that often in these really heavily managed areas where they’re doing a lot of this logging under the guise of fire mitigation it may actually be making fires worse.”

According to Tommy, “California does a great deal to protect communities from earthquakes, but we need to approach wildfire and climate change with the same level of science-based seriousness.”

Given the pressing need for action on this issue, we’ve provided some immediate resources and further action opportunities.

- To stay abreast of the of projects occurring within the Cleveland National Forest, you can visit this U.S. Forest Service website. And here is a link to the most recent entry for projects taking place as of September.

- If you’d like to help support Los Padres ForestWatch and its efforts to protect forests from logging projects, visit their website.

- You can e-mail Bryant or Jeff directly for more information. Bryant’s e-mail is bryant@lpfw.org and Jeff’s is jeff@lpfw.org.

- Download and share Bryant’s Powerpoint presentation via PDF file (FYI this is a large file). Here’s an easier to manage weblink URL for the file.

- View the Facebook video from Bryant’s Sept. 10th presentation to the Environmental Democrats.

- Visit the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) website for details and information about related projects occurring on state lands.

Because of the importance of the issue and the devastation that’s occurring, we will also announce the date of a workshop where you can learn more about how to get involved and make a difference on this critical environmental challenge.

Article photos and graphics courtesy of Bryant Baker and Los Padres ForestWatch.

Pino Alto grove banner photo atop Figueroa Mountain © 2006 Tommy Hough.