Like many Americans, my heart sank when the Carter Center announced the former president was entering hospice care after a series of hospital stays, rather than pursuing “additional medical intervention.”

At 98 years, Jimmy Carter is the oldest-living former president, and the president with the longest gap between his final year in office and current age. After a single four-year term, Carter was 56 when he relinquished the presidency to Ronald Reagan 42 years ago in January 1981.

My affinity for Jimmy Carter comes from a number of places. He’s been a role model since I was a boy. There’s his charitable decency as a human, his incredible post-presidential career, and the policies he pursued as president from 1977 to 1981, including:

- Carter’s pioneering advocacy of rooftop solar when he had 32 panels installed on the roof of the White House in 1979 (Ronald Reagan, in all intentional symbolism, had them removed two years later).

- A genuine foreign policy commitment to human rights.

- Wariness toward U.S. military adventurism in Central America.

- Seeking and making peace between Egypt and Israel.

- Truly leveling with the American people in national addresses, sometimes to his popular detriment.

- Boycotting the Moscow Olympics in 1980 over the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan.

- Moving to break from a reliance on foreign oil and fossil fuels.

- Keeping the U.S. out of war and at peace.

- Kickstarting the nation’s craft beer renaissance.

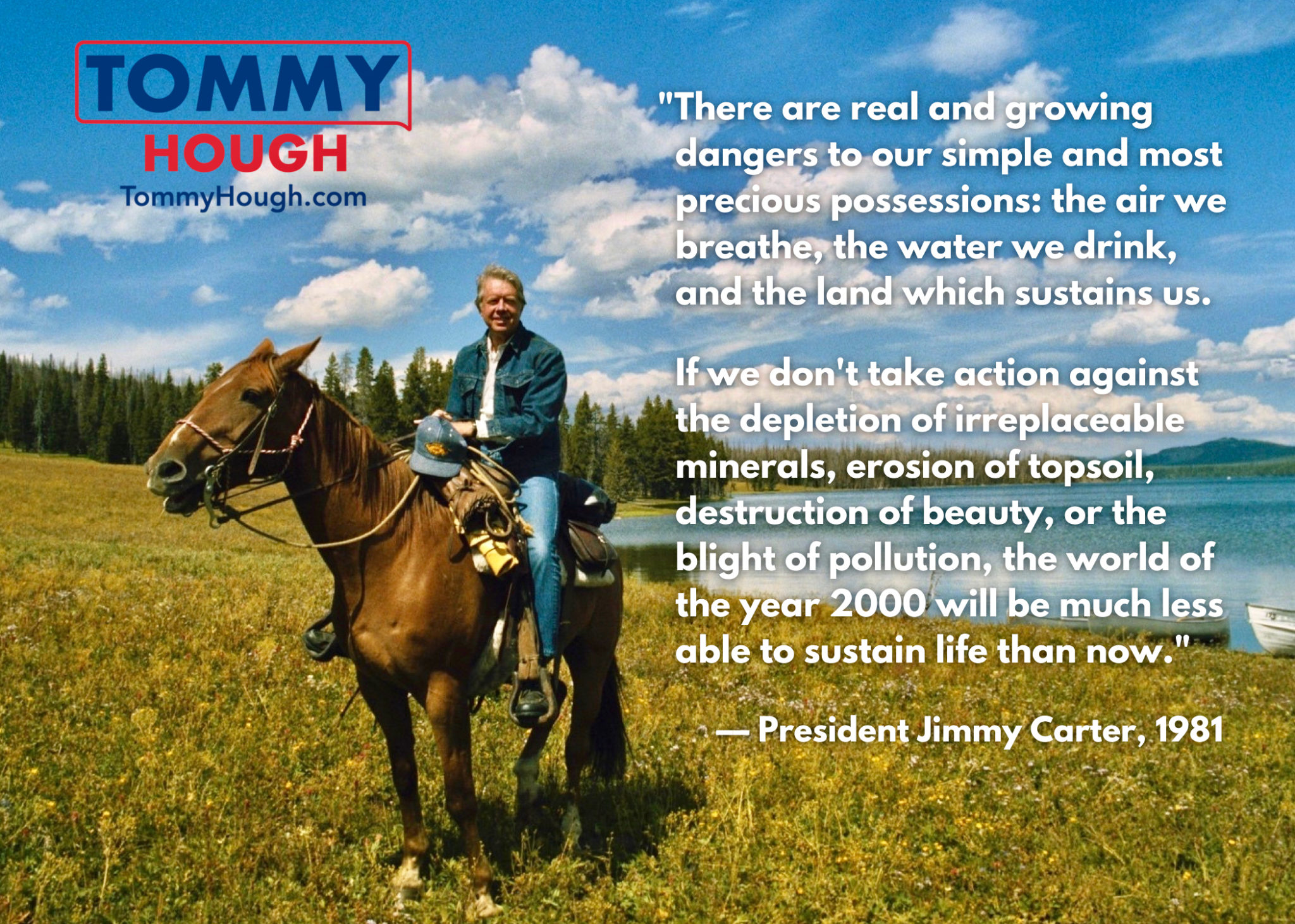

- An environmental and conservation legacy that culminated in the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980, which Carter has continued to advocate for and remains the largest-ever expansion of U.S. protected lands that more than doubled the size of areas managed by the National Park Service.

The Carter administration also imposed a surcharge on imported oil (Congress later rescinded it), proposed an Energy Mobilization Board (Congress ignored it), and successfully created the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which oversaw effective federal disaster response to the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in 1979 and the eruption of Mt. St. Helens in 1980 — itself leading to a National Monument declaration and the unprecedented preservation of a vast area where nature’s ongoing renewal is measured, researched and appreciated in real time.

Carter’s time since leaving the presidency has not only been the epitome of selfless service, but one of the finest modern examples of American activism, from monitoring elections in developing democracies, building homes for the unhoused with Habitat for Humanity, utilizing the Carter Center’s resources to prevent and eradicate disease, and even teaching Sunday school until he was physically no longer able to do so.

In interviews, questionnaires and forums I’ve long identified Carter as not only my favorite president, but “my first president.” Like many Generation X’ers, Carter’s election in 1976 was the first presidential election I remember, and its impact was a source of joy for my family.

I was born during the Nixon administration. Even though I was too young to understand what Vietnam and Watergate were, I remember being aware of them as constants in the background on the TV and radio as I played with my Six Million Dollar Man action figure or Matchbox cars and went about my kid business. There was always a drumbeat about the POWs, inflation, bombing, the energy crisis, gas prices, crime, all of which were eventually drowned out by the steadily-increasing clamor of Watergate.

Beyond being an office and residential complex along the banks of the Potomac River, Watergate took on a life of its own during the early 70s — and all roads led back to Richard Nixon. While he was re-elected in the biggest presidential landslide ever in 1972, the election occurred several months before the implication of the Watergate break-in had reached critical mass with the public. All that changed when televised congressional hearings began in the spring of 1973 and witnesses began to come forward.

My parents were Democrats, but beyond that they loathed Nixon — I mean loathed. My father couldn’t say Nixon’s name without making a face of deep irritation, and my mother simply referred to him as “the creature.” When Nixon at last announced his intention to quit, my mother allowed me to stay up past my bedtime on a humid summer evening to watch his resignation speech on TV. She felt it was important that I see it and remember it.

The next day, during what seemed like a daylong television event, I watched live coverage with my mother of Nixon leaving the White House. Hours later, we were still watching TV as the now-disgraced former president arrived at what was Marine Corps Air Station El Toro in Orange County, near Nixon’s “Western White House” in San Clemente overlooking San Onofre State Beach. For my mom, there couldn’t be enough of Nixon really being gone.

A month later, the unelected yet newly sworn-in President Gerald Ford announced he was giving Nixon “a full, free and absolute pardon” for all offenses, i.e. crimes, that Nixon had “committed or may have committed” while in office. To the nation, it was another betrayal. There was just no end to it: the war, the bombings, the burglaries, the crimes – and now, a pardon for the person who was revealed to have been so clearly behind so much of it. Nixon went into hibernation, and Ford’s nascent, accidental presidency never recovered.

For many Americans, 1976 not only marked the nation’s Bicentennial, but an opportunity to turn the page on the sorrow and dishonesty of the Vietnam and Watergate years. And for a growing number of voters, Jimmy Carter seemed to be the person to turn that page, positioning himself as a D.C. outsider after having served a single term as governor of Georgia from 1971 to 1975 — itself a clean break from that state’s Democratic old guard and segregated legacy.

Carter was initially tolerated, but never a favorite of the national Democratic Party establishment, which eventually tried to derail him ahead of the 1976 party convention (they tried again with Ted Kennedy in 1980). Unbowed, he struck a bold note of authenticity when he admitted to Playboy he’d “felt lust” in his heart, and without a hint of self-consciousness said through his toothy grin, “I will never lie to you.” Sounds corny, right? But after the trauma of Watergate, Americans needed to hear it, and it stuck. No D.C. insider, no matter how pious, could ever get away with such a sentiment. He seemed approachable. He fashionably admitted he even saw a UFO, calling it “the damndest thing.”

Carter’s ultimate win, and the narrowness of his margin of victory, was the closest U.S. election since the fabled match-up between Kennedy and Nixon in 1960. It was, in fact, one of the nation’s great electoral nail-biters when Americans went to bed without knowing who won. As a little boy I remember watching the returns and being fascinated by the electoral college map, and hearing about a new pseudoscience called “exit polling.” My parents, both Silent Generation liberals born in the 1930s, said little, kept their heads down and their distance from the TV, and quietly hoped.

The next morning when I woke up for school, my mother was elated. She told me Carter had won. That an honest man of some decency would really be president. She wept with relief and a quiet, restrained joy. I remember being particularly impacted by how happy my parents were at the news. They said it was like 1960 when Kennedy had won and the Pirates beat the Yankees in the World Series. For our home, it felt as though something positive had shifted in the universe, and a page had indeed been turned on the sadness and national trauma of the previous years.

Carter, of course, entered an office where he faced immense challenges at the outset. I’m not going to go into all the details of his single term, or try to convince you he was better than this president or that president — but here’s a takeaway as the 39th president enters his twilight as beloved an American as any: Jimmy Carter was the last president to truly level with the American people. He respected Americans’ intelligence, and spoke plainly with Americans instead of trying to terrify them or hustle them with the empty sunshine and platitudes that have become the tedious norm of American political life.

During the oil crisis of 1979 and 1980 — one of several issues, along with an uncooperative economy and the interminable Iran Hostage Crisis that sealed his administration’s fate — Carter chided the national habit of using a disproportionate amount of the planet’s resources, and recommended putting on a sweater and turning the thermostat down in his criticisms of the nation’s dependence on foreign oil.

In what has informally come to be known as his “Malaise Speech,” made from the Oval Office on July 15th, 1979, Carter voiced concern over the “crisis of confidence” Americans seemed to be feeling, noting the American middle class had everything, yet seemed to be happy with none of it. “In a nation that was proud of hard work, strong families, close-knit communities, and our faith in God, too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption,” said the president. “Human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns.”

“All the legislation in the world can’t fix what’s wrong with America,” continued the president. “What’s lacking is confidence and a sense of community.” Imagine for a moment a president saying such a thing today. Contrast that to the president telling a shocked American public following the Sept. 11th attacks to quit worrying and go spend money at the mall.

For Carter’s troubles, Americans voted him out in a landslide election in 1980 for another ex-governor who was more than happy to tell the voters what they wanted to hear, even as wages stalled, unions were demonized, and benefits trimmed. Carter’s loss marked an end to a political era, as Ronald Reagan began to privatize and deconstruct FDR’s New Deal as fast as it could be arranged. Reagan’s victory also marked the fuel-injected beginning of the empty calorie, performative politician for whom manicured TV appearances, smiling “toothpaste commercial” group photos, and social media likes has become the ultimate, sunny norm.

For me, Carter’s election in 1976 secured a belief in the pre-Citizens United power of elections and the electoral process, and the power of Americans to shift their country’s narrative when they make the choice to do so, clearing the way to truly build a more perfect union — itself one of the greatest expressions of humility ever committed to paper.

Cory and I are grateful for Jimmy Carter’s life of service to our country and our world, and his embodiment of the best of humanity and our national character. A role model for so many, he is indeed the epitome of grace. Perhaps, in his twilight, we are even learning something from him now.

We wish this most beloved American and his family love, comfort, and peace.