Born in 1940 and murdered barely two months after his 40th birthday in 1980, John Lennon has now been gone as long as he was with us.

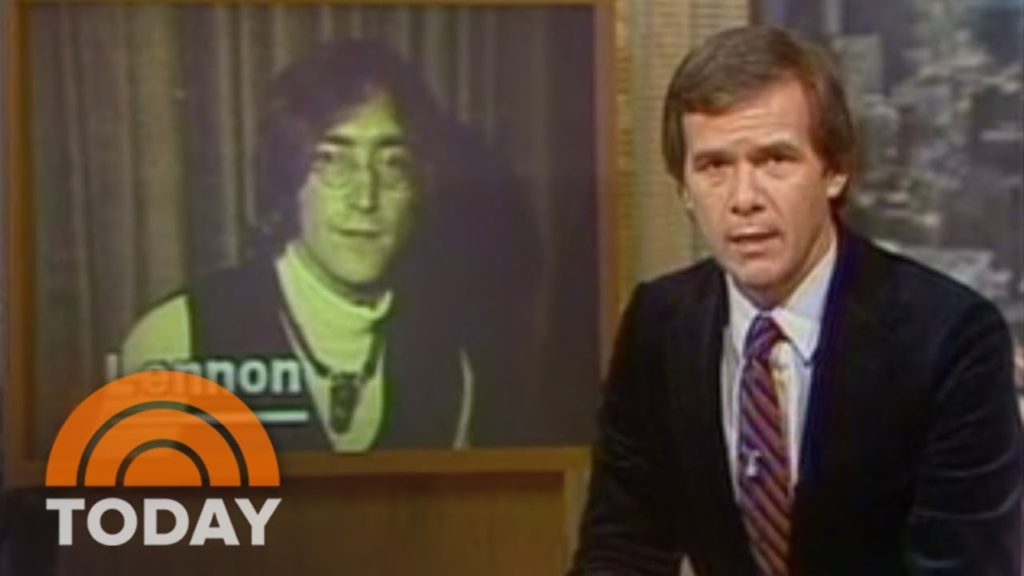

Forty years ago, just past 11 p.m. on December 8th, 1980, the world found out about the murder of John Lennon from Howard Cosell and Frank Gifford, as the Miami Dolphins played the New England Patriots on ABC’s Monday Night Football. Just as the game was about to go into halftime, Cosell made the first of two announcements about Lennon’s murder:

“We have to say it, remember this is just a football game, no matter who wins or loses. An unspeakable tragedy confirmed to us by ABC News in New York City. John Lennon, outside his apartment building on the west side of New York City, the most famous perhaps of all the Beatles, shot twice in the back, rushed to Roosevelt Hospital — dead on arrival. Hard to go back to the game after that news flash.”

It was as weird a pop culture moment as any that the world learned about one of the ultimate rock and roll tragedies from Howard Cosell, but it’s clear that Lennon’s murder affected Cosell during the broadcast, as he had welcomed Lennon into the Monday Night Football broadcast booth as a guest just six years earlier when Lennon was promoting his Walls and Bridges album in 1974.

I wasn’t watching Monday Night Football that night because I had to go to school the next day and was already in bed, but it was the first thing I heard about the next day when my clock radio went off and I woke up to the news of Lennon’s murder in between Beatles songs. I remember eating a bowl of cereal in stunned silence getting ready for school, watching the Today show.

I wasn’t watching Monday Night Football that night because I had to go to school the next day and was already in bed, but it was the first thing I heard about the next day when my clock radio went off and I woke up to the news of Lennon’s murder in between Beatles songs. I remember eating a bowl of cereal in stunned silence getting ready for school, watching the Today show.

I was knocked into such a deep state of shock I couldn’t even speak. I don’t remember arriving at school or talking about Lennon’s murder or anything else the entire day. Other than one idiot kid who ran around in the morning yelling about it, most of my classmates didn’t seem affected, if they knew at all. It was just a Tuesday.

But I knew, and I was devastated. When I came home from school that afternoon the shock had worn off. I dropped everything, the grief seized me, and I cried my eyes out for the next two days.

Perhaps it’s an indication of how good I had it growing up, because I can’t think of anything that traumatized me more as a boy than John Lennon’s murder. I had a happy childhood, surrounded by a great deal of music and a loving and thoughtful family, but the Beatles made me particularly happy. As much as I always heard what was playing on the radio and in the car, the Beatles were my band.

Lennon’s murder was the first time I felt as though something was ripped from me. It came without warning, and violently stripped away my innermost self in an overwhelming hemorrhage of grief and loss. I can’t recall anything else like it as a kid, and I can still feel that shock and hurt from 1980 bookmarked onto my internal chronology.

Having grown up on the Beatles, it was about four years before I could put on one of their albums again. There was just too much immediacy to the tragedy of Lennon’s murder for me to able to enjoy their music. So from the final weeks of 1980 to about the summer of 1984, I went into the only time in my life when I was in a “Beatles blackout,” where the band that meant so much to me as a boy had become too much to bear. It was just too sad.

When I finally began to emerge from my blackout and listen to the Beatles again, it was like rediscovering a beloved old friend with memories that went back years. I found I loved the Beatles even more. As a teen I was suddenly getting so much more out of the Beatles’ music than just the happy vibes of my childhood, and it was a wonderful sense of renewal and discovery that helped me put Lennon’s murder, however awful, into a sense of place and perspective.

From there I began to explore the Beatles’ solo material, in addition to all the other music I’d been listening to in the intervening years that I’d also come to love. But it was such a joy to reconnect with the Beatles, and like millions of others around the world I carry their music inside my head and heart today. Like all the music and songs I treasure that have been part of my life, the Beatles have been there for me in good times and bad, and when I’ve needed them the most.

An Erased Entry

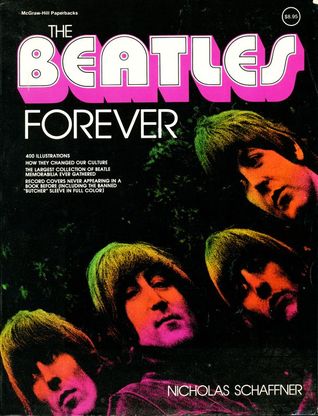

As a boy I had a copy of Nicholas Schaffner’s 1977 book The Beatles Forever, which my parents had given me for my eighth birthday. I devoured the book and pored over it, and it was a constant companion.

As a boy I had a copy of Nicholas Schaffner’s 1977 book The Beatles Forever, which my parents had given me for my eighth birthday. I devoured the book and pored over it, and it was a constant companion.

Within days of Lennon’s murder in December 1980 I wrote about his death in the book’s flyleaf, ahead of the title page. This was unusual because I never wrote in books or on album covers, but for some reason I was compelled to write, in pencil, about Lennon’s death and “report” the news of his murder and my feelings about it. I even dated the entry.

For some reason, I erased the entry a few years later when I was returning to enjoying the Beatles’ music. I’m not sure why, but I remember doing it. Perhaps it was my way of gaining some control over how Lennon’s death had affected me, or perhaps I simply wanted to enjoy my copy of The Beatles Forever as I had before Lennon’s life was taken from him.

I don’t think I was embarrassed about what I’d written, but a 15-year old kid doesn’t necessarily look at what an 11-year old kid may have written with some sense of posterity. It’s too bad I didn’t save what I wrote somewhere, because the kid who wrote that entry in his Beatles book in 1980 was still reeling from shock and emotional duress, and all these decades later I would’ve liked to have known what he thought and how he tried to resolve it.

Reagan at the Dakota

I’ve never been able to find TV news footage of this on-line, but in the days after John Lennon’s murder I remember seeing Ronald Reagan on TV at the crime scene at the Dakota on New York City’s Upper West Side, where Lennon and Yoko Ono lived.

I’ve never been able to find TV news footage of this on-line, but in the days after John Lennon’s murder I remember seeing Ronald Reagan on TV at the crime scene at the Dakota on New York City’s Upper West Side, where Lennon and Yoko Ono lived.

At the time, Reagan was the president-elect, having just won a landslide victory over incumbent Jimmy Carter the month before. Reagan likely stopped by the Dakota because he was in New York on some other business, or perhaps he was visiting one of the many celebrities who also lived in the landmark New York City building.

However much Reagan may have been loathe to admit it, millions of Beatles fans had just voted for him as president, and no doubt he or someone on his team thought it was a good idea for him to be seen and pay his respects, especially since the nation was in a state of collective mourning.

But it always struck me as odd that Reagan was there at all, as though he had any connection to the Beatles other than railing against their music and long hair, and as though he wasn’t anything less than complicit in his awareness of the Nixon administration’s surveillance of Lennon just a few years earlier.

I remember Reagan saying something about Lennon’s murder being a tragedy, which it obviously was. I also seem to remember him being asked if Lennon’s murder had changed his opinion on the easy availability of handguns in the United States.

I may be conflating the timing and locale of Reagan’s remarks as president-elect, but I recall Reagan said his position on handguns had not changed, which I found outrageous since he was at the very site where John Lennon had four hollow-point rounds blasted into his back by a deranged assailant obsessed with Catcher In the Rye, and who believed Lennon himself was some kind of an “imposter.”

Of course, a little more than three months later, Reagan himself would be shot by a .22 caliber handgun in the hands of a deranged assailant obsessed with Jodie Foster’s role in the 1976 Martin Scorsese movie Taxi Driver. In addition to wounding three others and ultimately killing White House press secretary James Brady decades after the shooting, we now know the 1981 assassination attempt nearly killed the 40th president.

Reagan was lucky in 1981. In 1980, John Lennon was not.

A Few Favorite Lennon Solo Songs

“Mind Games” (1973)

One of my favorite John Lennon solo songs is the title cut from his 1973 album Mind Games. Lennon seldom ventured into the dreampop he was so adept at after “I Am the Walrus” and the White Album’s “Cry Baby Cry,” but “Mind Games” is a wonderful song that’s more metaphysical than a critique on the unfortunate earthbound human practice.

One of my favorite John Lennon solo songs is the title cut from his 1973 album Mind Games. Lennon seldom ventured into the dreampop he was so adept at after “I Am the Walrus” and the White Album’s “Cry Baby Cry,” but “Mind Games” is a wonderful song that’s more metaphysical than a critique on the unfortunate earthbound human practice.

I remember hearing this as a kid on 1020 KDKA while I was in the back seat of my parents’ giant 1970 Chrysler Newport, and I’ve cherished it ever since, especially the good-natured throwaway but still meaningful closing line of “I want you to make love not war. I know you’ve heard it before.”

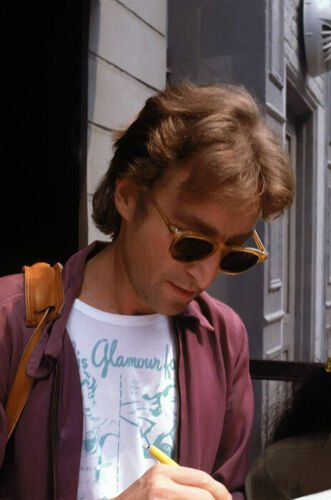

The official video since released for the song was actually filmed a year after the “Mind Games” single and album came out, with Lennon walking around Central Park on a golden autumn afternoon on his way to a performance of the now-forgotten off-Broadway production of Lonely Hearts Club Band On the Road, which at the time was playing at the Beacon Theater at Broadway and West 74th Street.

“Stand By Me” (1975)

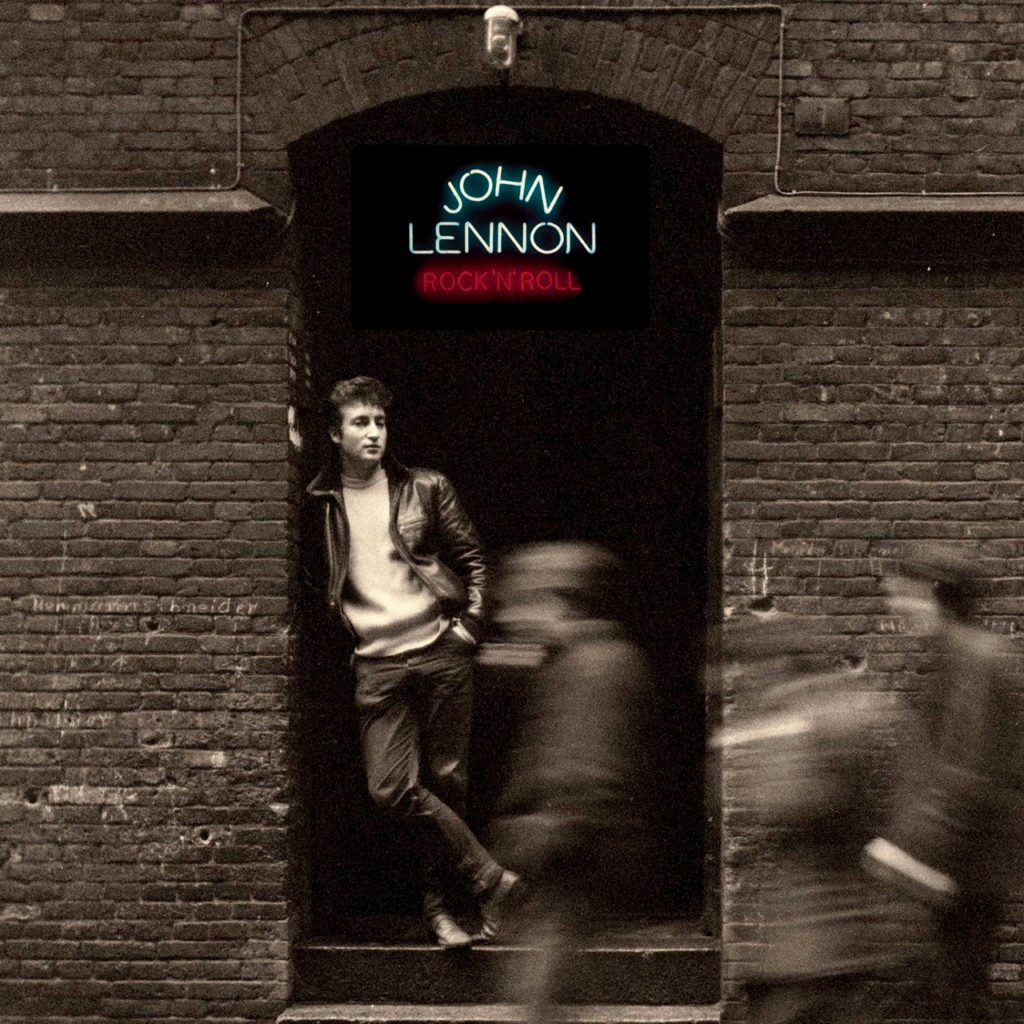

John Lennon’s cover of the 1959 Ben E. King classic was recorded for his Rock ‘n’ Roll album of 50s and early 60s rock and roll covers, which he was working on with co-producer Phil Spector intermittently throughout his “Lost Weekend” period, and which was eventually released to the public in early 1975.

John Lennon’s cover of the 1959 Ben E. King classic was recorded for his Rock ‘n’ Roll album of 50s and early 60s rock and roll covers, which he was working on with co-producer Phil Spector intermittently throughout his “Lost Weekend” period, and which was eventually released to the public in early 1975.

The arrangement Lennon opted for was typically big for the era, and in lesser hands could have run the risk of turning into a campy, Vegas-style vamp. But Lennon wisely opted to keep his powder dry on the verses and leaned into the emotional rave-ups on the chorus, with the sparse opening of Lennon’s acoustic guitar and accompanying organ paving the way for what became one of his greatest, most urgent solo vocal performances that enabled him to truly remake the song in his own image.

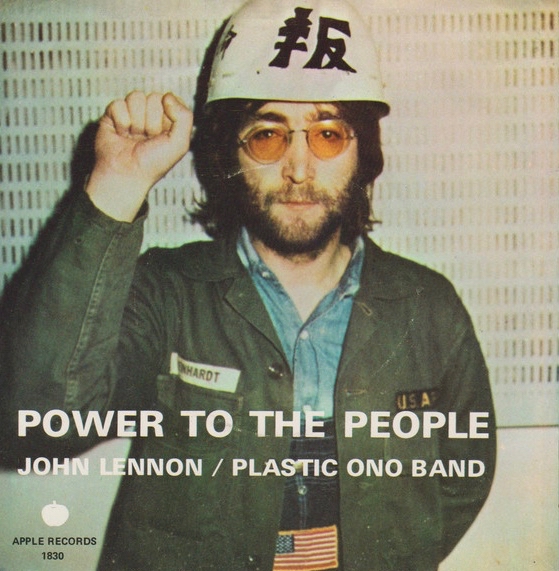

“Power to the People” (1971)

Years after this single came out, Lennon admitted some of the songs he wrote and positions he espoused as part of his radical leftist phase in the early 70s was to enable him to move past his Beatles identity and be taken more seriously as a songwriter by radical icons of the era like Angela Davis and John Sinclair. Lennon said he saw it as an extension of his “Working Class Hero” identity, even though the other three Beatles acknowledged Lennon grew up in far more of a middle class setting than the rest of them did.

Years after this single came out, Lennon admitted some of the songs he wrote and positions he espoused as part of his radical leftist phase in the early 70s was to enable him to move past his Beatles identity and be taken more seriously as a songwriter by radical icons of the era like Angela Davis and John Sinclair. Lennon said he saw it as an extension of his “Working Class Hero” identity, even though the other three Beatles acknowledged Lennon grew up in far more of a middle class setting than the rest of them did.

Nevertheless, Apple released this stomping, crowd-pleasing single in early 1971, eight months before the release of Lennon’s benchmark Imagine album. It wasn’t exactly a continuation of “Revolution,” but it celebrates taking it to the streets and the rights of working families, while calling out leftist allies for behind-the-door misogyny.

“Oh Yoko” (1971)

This lovely, melodic, folk rock number from Lennon’s 1971 Imagine album got a second lease on life when it appeared in the soundtrack of Wes Anderson’s 1998 movie Rushmore, and it’s gone on to be appreciated as one of Lennon’s classic solo tracks and a heartfelt ode to his wife.

This lovely, melodic, folk rock number from Lennon’s 1971 Imagine album got a second lease on life when it appeared in the soundtrack of Wes Anderson’s 1998 movie Rushmore, and it’s gone on to be appreciated as one of Lennon’s classic solo tracks and a heartfelt ode to his wife.

While the Imagine album is loaded with some of Lennon’s best solo melodies and songs like the vulnerable “Jealous Guy,” the vitriolic realpolitik of “Gimme Some Truth,” the cruel putdown of his former songwriting partner in “How Do You Sleep,” and the full-on jam of “I Don’t Want to Be a Soldier,” the happy, puppy dog domesticity of “Oh Yoko” closes the album with a pitter patter of swirling pianos, acoustic guitars, and harmonicas.

“I’m Losing You” (1980)

Recorded as part of the Double Fantasy sessions in the summer of 1980, this grinding version of “I’m Losing You” features none other than Cheap Trick backing Lennon, but for some reason this take didn’t make the cut to appear on the final version of the Double Fantasy album, as Lennon opted for a later recording of the song featuring many of the New York session musicians he’d worked with on previous albums.

Recorded as part of the Double Fantasy sessions in the summer of 1980, this grinding version of “I’m Losing You” features none other than Cheap Trick backing Lennon, but for some reason this take didn’t make the cut to appear on the final version of the Double Fantasy album, as Lennon opted for a later recording of the song featuring many of the New York session musicians he’d worked with on previous albums.

Fortunately, this version of “I’m Losing You” was made available on the John Lennon Anthology box set in 1998, and on the smaller, single-disc companion Wonsaponatime, showing the grit with which Lennon was returning to recording and songwriting in 1980 after a five-year absence from record making, which in those days was akin to an ice age.

“Bring On the Lucie (Freda People)” (1973)

Following the landslide re-election of Richard Nixon in November 1972, Lennon began to return to a more personal style of songwriting and away from the rock and roll radicalism that earned him a spot on Nixon’s “enemies list.”

Following the landslide re-election of Richard Nixon in November 1972, Lennon began to return to a more personal style of songwriting and away from the rock and roll radicalism that earned him a spot on Nixon’s “enemies list.”

Nevertheless, even as he whipped marvelous new state-of-the-relationship songs into shape for his Mind Games album like “Out the Blue,” “I Know,” and the dreamy “You Are Here,” he still had a parting shot for Tricky Dick in the form of “Bring On the Lucie,” which initially appeared to have been inspired by the murderous hostage-taking escape of the Soledad Brothers from the Marin County Courthouse in 1970.

Lennon streamlined the “freda people” lyrics into a near-dialogue with an imaginary Nixon in four of the song’s six verses, speaking directly to early 70s Law and Order paranoias. With shouts of “stop the killing,” and charging the song’s antagonists with slipping and sliding “down the hill on the blood of the people you killed,” Lennon indicted the Nixon administration for the waves of B-52 strikes on North Vietnam in December 1972 that forced Hanoi back to the bargaining table, but which caused an uproar among world leaders who said Nixon and the U.S. had committed war crimes (they had). Even at that time, the extent of the U.S. Air Force’s ongoing, secret bombing of Cambodia hadn’t yet been revealed.